Since my last post about the London shipwreck, many of you have been leaving some fantastic questions for me on our Twitter and Facebook pages, as well as on the comments section of our blog. For today’s post, I have tried to answer as many of them as possible and have included a little update on our progress at this stage of the project.

I am happy to say that I have managed to answer most of your questions here. A few that I received were very similar so I have addressed any questions that were along the same lines within one answer. Also, if you asked a question that I haven’t answered here, don’t panic! Take a look on the London Shipwreck page of our website www.southendmuseums.co.uk or my last blog post, as any questions which I haven’t answered here are already addressed in these places.

Okay, here goes…

Can you explain what is meant by a ‘Second Rate Ship’?

Dating from around the start of the Stuart era, a system developed of grading the fighting ships of the Monarch’s navy into several ranks or ratings. Ships ranged from ‘First Rates’ right through to ‘Sixth Rate’ vessels and the London herself was ranked as a Second Rate.

In the English Navy, a second rate ship was a ship of the line that usually had two gun decks. The term in no way implied that they were of inferior quality. They were essentially smaller and hence cheaper versions of the three-decker first rates. Like the first rates, they fought in the line of battle, but unlike the first rates, which were considered too valuable to risk in distant stations, the second rates often served also in major overseas stations as flagships.

CGI Image of the London © Touch Productions

What is the historical context relating to the London? What was life like for the sailors?

This is a fantastic question because one of the main motivations behind the work of archaeologists and historians is to find out about the lives of the people behind the objects.

In terms of historical context, the London was both built and sank within the 17th Century, an eventful and exciting period in British history. The century witnessed the Gunpowder Plot in 1605, the ‘Eleven Years Tyranny’ of King Charles I between 1629 and 1640, and the Second English Civil War. The country was also ruled as a republic for a period of eleven years, with Oliver Cromwell as the Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England. England fought three wars with the Dutch, survived the Great Plague of 1665-66, and fought the Great Fire of London in 1666. Of course, the Restoration in 1660 saw King Charles II returned to the throne, an event which the London was directly involved with, and the Scientific Revolution saw physicians, mathematicians and philosophers conducting the first scientific experiments to test the long-accepted theories of the Greek philosophers.

Conditions on board a naval warship during the 17th Century would have been cramped, low and damp and rife with disease, sickness and lice. Men of higher rank would have had their own, small cabins offering a certain level of privacy, but the lower ranking sailors would have slept in hammocks in shared cabins. The Captain would have been lucky enough to enjoy a private ‘quarter gallery’. The seamen usually drank beer and ate biscuits, cheese, salted-beef, peas and fish, whereas Captains often brought aboard their own provisions and had their meals cooked separately. During their off-duty time, seamen relaxed by swapping jokes and tales, gambling and playing games.

Storing wet finds in our archaeology stores. ©LukeMair

What are you most excited about finding and how many things do you think you will find?

These questions come from our Facebook competition winner Sam Robertson and her children Alice and Lewis. Congratulations to you all!

We have already had some really great finds brought up from the site and we expect more of these types of items. Some of the expected finds include personal items such as leather shoes and navigational dividers, buckets, pots and cooking utensils, ship fixtures and fittings such as door latches, as well as ordnance such as cannon balls. What I am most excited about finding, however, is anything that might be able to tell us a little bit more about what life was like on board the ship, as well as anything that could provide us with some more insight into the English Navy at such an interesting period in our country’s history.

The Thames is a great preservation environment due to the fact that all of the silt is able to exclude oxygen, which is a major factor in the process of decay. On the one hand, this could mean that we might expect to find quite a wealth of material. However, we are also faced with the fact that the fragile remains are starting to become exposed by the shifting sediment levels and much of it is being washed away by the tides and subjected to the effects of marine micro-organisms and the current shipping activity. It is for this reason that, whilst we are excited by the possibility of the finds we might be able to bring up, the most exciting aspect of the project, for us, is the opportunity to record everything that we can see down there. In fact, one of the primary aims of this season’s excavations is to record the site as effectively as possible, with plans for next year to see more extensive excavation.

Working on storage for the finds with the Museum Conservator. ©LukeMair

Could some of the timber be salvaged and put on display, or create a model of the ship out of salvaged timbers?

Over 350 years of being underwater has made both the ship and its associated objects very fragile. This is particularly the case with the timber and other organic materials. Due to their nature of rapid decay, it is usually far rarer to find organic materials on any archaeological site than it is to find metal or stone objects, for example, and the fact that the silty environment of the Thames Estuary has preserved some organic materials for us is very important and exciting!

Nevertheless, they are still very delicate. With the timber, water has replaced the cellulose that the wood was comprised of, meaning the cells have become waterlogged. This means that the wood is very fragile, soft, heavy and ‘squidgy’. We must always be extremely gentle when handling waterlogged wood, as it is so easy for parts of it to break away or to leave finger impressions.

For any archaeological wood or timber to go on display, a remedial conservation treatment process is required using a wax-like compound called Polyethylene Glycol (also known as PEG). The PEG is used to replace the water that has flooded the cells; however, the PEG must be sprayed onto the wood numerous times. At first, it must be very heavily diluted with water and, gradually, with each spraying, the PEG ratio increases, whilst the amount of water used decreases. As you might imagine, the whole process is exceptionally costly and lengthy. PEG treatment has actually been used on the Mary Rose and her associated wooden objects and the whole process, which started in 1986, is only projected for completion in 2015. That’s nearly 30 years!

The excavations this year are largely investigative, with recovery mostly of smaller finds. Next year will see more extensive excavation and the recovery of any larger objects, which may include some timber but is dependent upon what the archaeologists are able to achieve at the time. The licensed diver has recovered some small examples of some of the timber on previous dives so there is some potential to have some on display; however, we will be able to identify which finds we will definitely be putting on display once this season’s investigations are complete.

Documenting finds with the Museum Conservator. ©LukeMair

Please can you tell me how you choose your storage methods?

This is another really great question, as not many people are aware of the vital role that correct storage methods play in the preservation of fragile archaeological material.

As I mentioned in my previous post, a selection of the finds recovered will undergo full, remedial conservation and go on display at Central Museum. This, in itself, is actually a form of storage, as we must ensure that the objects are safely mounted and that the cases are set to the appropriate temperature, relative humidity and lighting levels.

For finds which will undergo preventive conservation and go into storage, much of it will need to be stored wet. When any waterlogged archaeological material is brought out of its marine environment, the effects of uncontrolled drying can be devastating. This is particularly the case for organic finds, as water often replaces the cells and components that the materials are originally comprised of. For example, leather finds can become brittle and split, iron can result in a potent corrosion reagent, and dissolved marine salts that have infiltrated porous stone and pottery can crystallize and cause cracking and splitting known as lamination.

Remedial conservation techniques can help to prevent this from happening when the objects undergo controlled drying but, for storage, we have to keep the objects immersed in chilled water in airtight Stewart boxes (these are similar to tuppaware containers). We include a layer of bubble wrap (bubble-side down) on the surface of the water to exclude oxygen and seal the containers with Parafilm (also known as Labseal) to further ensure the container remains airtight. We then label the box and record the work that has been undertaken on it before storing it in cool, darkened conditions. We have some excellent archaeology stores at Southend Museums that are subject to regulated humidity, temperature and lighting controls to ensure it remains the best possible environment for keeping the objects. Of course, the finds undergo regular, recorded water changes and monitoring to ensure they remain safe and stable and are always made accessible for research.

©LukeMair

What other types of archaeology are there in the Thames Estuary?

Thank you to our Twitter competition winner, Claire Brooks, for this question.

The Thames itself has played a crucial role both past and present as a major maritime route and boundary, an economic and fresh water source, a source of food and, in more recent times, a leisure facility. As you might imagine, there are an incredible number of archaeological sites within the river.

The London herself was rediscovered in 2005 during archaeological investigations for the Environmental Impact Assessment undertaken in advance of the works for the London Gateway project. The London Gateway is a major development of a new container terminal built on the north bank of the Thames, as well as a capital dredging scheme accompanying its construction in order to increase the depth of the navigable channel to the new port. Archaeological investigations were undertaken within the navigation channel and the dredge impact area only and, within what is a relatively small percentage of the whole river and estuary, a total of thirty archaeological sites were identified. Several of these are wreck sites, the London herself being just one of them. Some of the other sites include HMS Aisha, HMT Amethyst, The SS Letchworth, a German Aircraft, an ‘Iron Bar Wreck’, an Anti-submarine Boom, an ‘Ancient Wreck’, a ‘Pottery Wreck’, the Atherton, the Dovenby, and MV Ryal. Incidentally, as the repository museum for this area of the Thames Estuary, any archaeological material will be coming to Southend Museums.

If you would like to find out more about the sites investigated for the project, I’d recommend reading the publication for these investigations: London Gateway: Maritime Archaeology in the Thames Estuary, by Antony Firth, Niall Callan, Graham Scott, Toby Gane and Stephanie Arnott.

If you are interested in finding out more about other archaeology found in the Thames, you could take a look at the work of the Thames Discovery Programme. This is an ambitious project hosted by MOLA aimed at training volunteers to monitor and record the foreshore archaeology of the Thames and to communicate an understanding of the historic river to the widest possible audience. Head over to the Riverpedia page of their website to see the results of some of their investigations: http://www.thamesdiscovery.org/riverpedia/

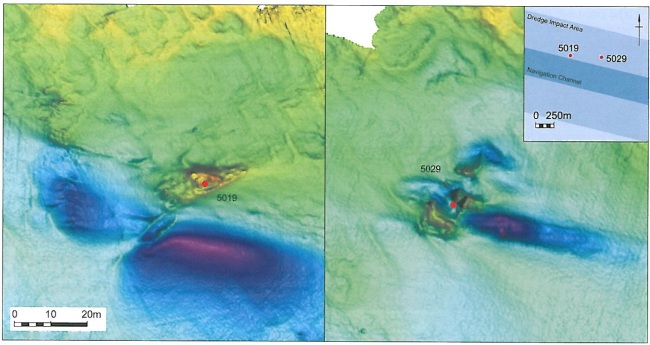

Multibeam bathymetry images of sites 5019 and 5029, the London. ©Wessex Archaeology

I hope I have answered all of your questions as clearly and concisely as possible here. I am aiming to keep you all as updated as possible on what we are doing and how the project is progressing.

Throughout next week the archaeologists and licensed diving team will be back on site for the second phase of this year’s investigations. Hopefully, they will have some great weather and diving conditions to enable them to conduct their work as effectively as possible. They will be bringing any finds to the museum, where I can undertake some preventive conservation and storage.

Some of the objects that will undergo remedial conservation are already with the conservators from English Heritage and I will be visiting them in Portsmouth in just over a week to discuss the best treatment options.

Finally, today marks the closing date for applications to volunteer for our community project with the London. We have had some excellent applications from some truly wonderful volunteers and we will be contacting them all shortly to arrange some meetings and training.

So, that’s all for now folks, but keep an eye out on our Twitter feed and Facebook page next week for all of the latest news as and when it happens. Look out for my next blog post too, as I will be letting you all know about the work we will be doing with our freshly recruited volunteers…

#LondonWreck1665